Layers of paint

In our bookshelf we have an issue of a new literary magazine, Schwalbe, with the theme “Literature, money, power and activism”. One of the articles is titled “Is literature left or right?”, an account of a conversation between some contemporary writers who profile themselves as leftist or right-wing. 'Is literature totally autonomous, does it live under the yoke of a meddling government or is it a slave to commerce? And as a writer, are you actually still allowed to say anything? Isn't literature just a left-wing nest?', the introductory text reads. The conversation turns to ideological gatekeeping, prudishness and how left and right are said to symbolise equality and freedom. While I read the piece, I am reminded of a well-known long-haired author who calls himself pretty leftist who sat next to me during a lecture, fulminating about how sorry he was that in this “woke culture” he is no longer allowed to say the n-word. When I called him on it and asked why it was so important to him to be able to say that word wherever he wants, whenever he wants, he remained silent. Apparently, freedom can be bought in the dollar store for a few pennies and to the liberals who build their entire ideology around it is nothing more than an empty shell.

The conclusion of both the left-wing and right-wing writers? Literature is there to break taboos. Anything should be allowed in literature, because it belongs to everyone. The n-word? According to their views, that should be allowed. Racism, misogyny and other violations of human rights are fine, as long as both the left and the right cover it with three thick layers of literary or artistic paint.

The Extremely Special Gift

Recently, I stumbled upon a self-proclaimed Marxist who was a staunch supporter of the works of the Marquis De Sade. The cognitive dissonance could not be any greater. The French author is proven to have tortured and mutilated a multitude women but is still put on a shining pedestal by the “left” because of his ‘literary talent’ and his ‘revolutionary literature’ - as if the man, a born aristocrat, single-handedly led the revolution with his Extremely Special Gift and his fly open. During the Ancien Regime, De Sade belonged to the elite, so he knew full well that the revolution could cost him his head (literally). Having been imprisoned several times during the old regime for his crimes against women, he could easily play the revolutionary aggrieved by the old oppressor. Note: even in the old days, it was virtually impossible for a female victim to charge someone belonging to the elite for abuse. This makes the fact that De Sade has been jailed several times for his crimes even more pressing - he will have been so crude that it was unjustifiable even within the elite. De Sade was a ‘revolutionary’ until Marat discovered what this man had been jailed for, of course - misogyny has no place within a new, equal society. He placed De Sade on a list of counter-revolutionaries and had him tracked down. However, De Sade crawled through the eye of the needle as someone else with the same name was accidentally executed. Not much later, Marat was murdered himself by Charlotte Corday and it would take several more years before De Sade would be arrested for his counter-revolutionary activities. But, even then, he was imprisoned for conspiring against the revolution - not for the countless female victims he now had to his credit. Within leftist circles, De Sade is still seen as a champion of free speech and the archetypal breaker of taboos. Our art-loving Marxist even questioned: where would contemporary literature have been without these champions of freedom? Freedom for men, of course, because for women, freedom means mainly that men are free to use them.

Deaf as a post, baby

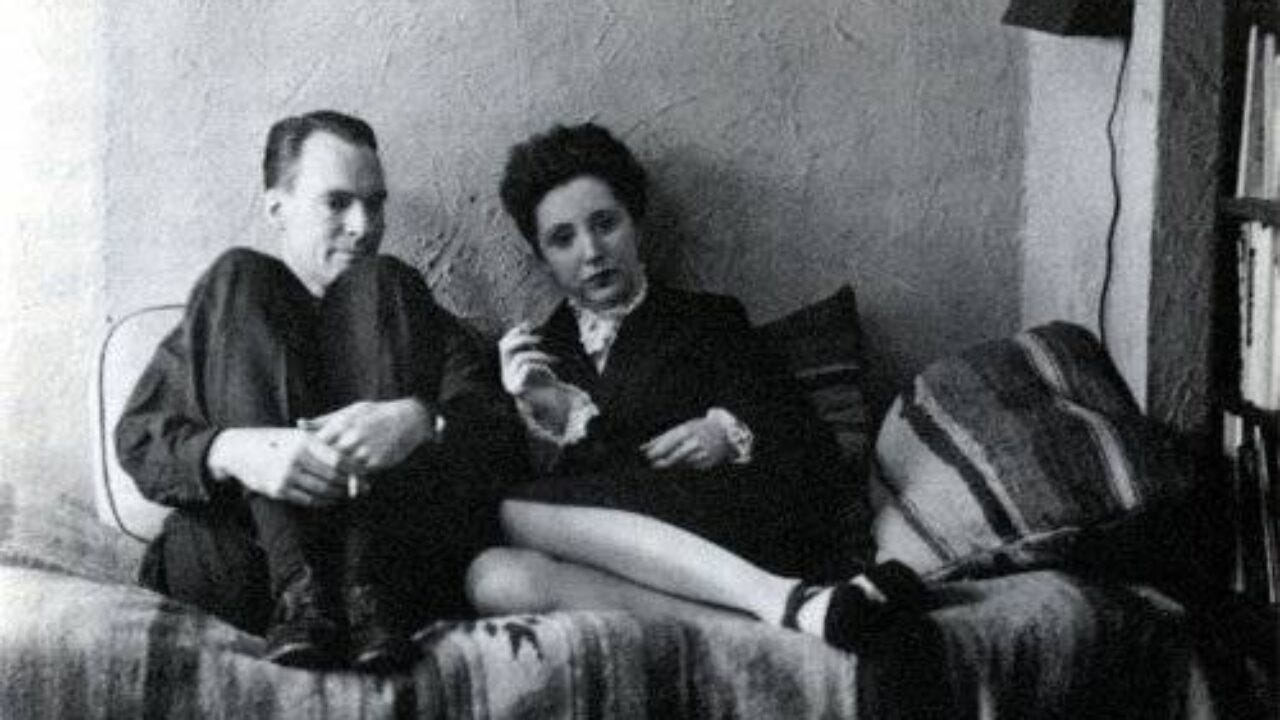

Henry Miller is also seen as a kind of patron saint of freedom and one of the great literati of modern times. I have always been fascinated by Anais Nin's interest in Miller's rough behaviour - she looks at it from a distance, as if it were something sublime. The abyss, the horror and their attraction. They fight over the same woman, June, who for Miller is primarily an object of lust and for Nin is the woman she would like to be. For Nin, sexuality is often a means of self-discovery and spiritual or emotional expression. She engaged in a kind of intimate, poetic exploration of relationships that emphasised connection rather than merely physical satisfaction.

As I try to struggle through Tropic of Cancer, I wonder: is it a coincidence that the woman who abused my husband was so fond of Miller? Is it a coincidence that the most sexist men I know see in Miller an exciting anti-hero? I tried to read Sexus two years ago, but I couldn't get through it. Generally, back then, I still thought that literature was a kind of outer category, a place where anything goes. I couldn't put my finger on why I couldn't get through that book. I just assumed I must be a prude, not much of a true artist and a lousy leftist. Now that I have almost made it through Tropic of Cancer, Miller's “raw, taboo-breaking and innovative style” pretty much boils down to this:

According to Miller, a woman’s primary value in their sexual appeal or ability to satisfy male desire. They are subservient to male pleasure and their personalities are often neglected in favor of focusing on their physicality. In Tropic of Cancer, women are depicted as tools for Miller's self-gratification, and their emotional complexity is frequently ignored or trivialized:

‘Who wants a woman to have a mind in bed?’

Or:

‘It’s just a crack with hair on it, it’s disgusting. You can get something out of a book, even a bad book, but a c*nt is just a c*nt, it’s a waste of time’

Miller contrasts women with men in a way that reinforces the idea that women are not fully human or that their emotional depth and intelligence are secondary to their roles in sexual and romantic relationships. His writing about his relationships and affairs reflect a sense of entitlement and a lack of respect, often complaining about women taking his freedom to do as he pleases. To think of the countless times a male artist whined to me about his partner being an obstacle to their ‘freedom’ makes my blood boil.

Of course it’s important to consider the historical and cultural context in which Miller was writing. The mid-20th century was a time of significant gender inequality, and Miller's works reflect the gender dynamics of his era. While he, the male-artist-as-genius, may have felt liberated in exploring human sexuality in a way that was unconventional at the time, his depictions of women often mirrored the patriarchal attitudes that were prevalent in society. Again: in propagating radical freedom and breaking taboos, who is actually free? Is it an actual taboo to put the sexual status quo on steroids and write about it, so that men can publish it and men can consume it? His response to feminist critiques in the 1960s and 1970s - if he responded at all - was often dismissive and denigrating. I would have loved to embrace Anais Nin and tell her to give up – no psychoanalysis is going to clear up the messy picture of Henry Miller. He’s deaf as a post, baby.

Balloon

Is literature left or right? Is literature really about breaking taboos? I think it is much less vague than the writers in the literary magazine make it seem. Progressive literature tests the status quo, questions prevailing values and norms. Conservative literature does the opposite, or at worst inflates the status quo into such a big balloon that it obstructs everyone's clear view of a sensitive subject, as quite a few of our hailed literati do. But like any balloon, the brightly coloured and beautifully made shell is filled with air and Libertas will do everything in its power to puncture it.